What works. Can we know?

The wonderful @TessyBritton brought my attention to this article by Dr David Halpern, CEO of the Behavioural Insights Team, on the rise of the What Works Centres (WWC). The rise in appetite for evidence in public policy is long overdue, and hugely welcome in terms of designing for delivery of improved outcomes for (with) the public. So we’re watching the work and influence of the WWCs with great interest.

But. But. Whilst being a massive enthusiast for evidence, there’s something about the focus on ‘what works’ that worries me. Is it possible that, like valuable new arrivals before it (programme management disciplines for example), it becomes embraced as a silver bullet, with possible unintended consequences?

The final paragraph in the section in the article on the Education Endowment Foundation provides illustration:

“The EEF has produced a toolkit aimed at schoolheads, teachers, and parents. This summarises the results of more than 11,000 studies on the effectiveness of education interventions, as well as the EEF’s own world-leading studies (http://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/toolkit/).For each educational approach, such as peer-to-peer learning or repeating a year, the toolkit summarises how much difference it makes (measured in months of additional progress); how much it costs (assuming a class of 25); and how confident they are of the effect, on the basis of the evidence so far.

Headteachers can therefore base spending decisions on robust evidence about their impact on pupils. For example, it turns out that extra teaching assistants are a relatively expensive and in general not very effective way of boosting performance, whereas small group teaching and peer-to-peer learning are much more cost effective. Repeating a year is expensive and, in general, actually counterproductive.”

Sounds sensible as a basis for decision making in schools? As Prof Dylan Wiliam (well worth a watch speaking at ResearchEd2014 here) notes, “Research can only tell us what might be“:

“The research on homework shows that most homework does no good. But then most of the homework that teachers set is crap. So what the research really shows is that crap homework does no good. Big shock there! But what the research also shows is that the homework that teachers set most frequently is the least effective. Preparation for future learning is the most effective form of homework; it’s just much more difficult to organise. So the fact that people have said that the homework research shows that homework doesn’t do any good, doesn’t mean that homework can’t be good.”

The Teaching Assistant issue is very similar. We know that TAs do not accelerate learning, especially if – as the least qualified adults in the classroom – they are deployed with little training, to spend time with the most struggling children. This is the evidence that lies behind the EEF’s toolkit’s assertion that TAs cost a lot and don’t boost performance much. But as Ben Goldacre says, “I think you’ll find it’s a bit more complicated than that”: 2 more recent RCTs commissioned by the EEF itself and published in Feb 2014 concluded that TAs can improve literacy and numeracy skills when they are deployed well:

“Research to date has suggested that students in a class with a teaching assistant did not, on average, perform better than those in a class with only a teacher. The new findings suggest that, when used to support specific pupils in small groups or through structured interventions, teaching assistants can be effective at improving attainment.”

It’s really, really important that we embrace high quality existing research, and in particular learning from repeated trials and Big Data. But in so doing, we must be intelligent about what this evidence does and does not tell us. The ‘low impact for high cost’ conclusion of the EEF toolkit is based on a simple economic measurement of value for money of teaching assistants. Is this really telling us ‘what works’? Dylan Wiliam again:

“[In education] ‘what works?’, which is what politicians would love to know about, is the not the right question, because [in education] everything works somewhere and nothing works everywhere. The interesting question is ‘under what conditions does this work?’“

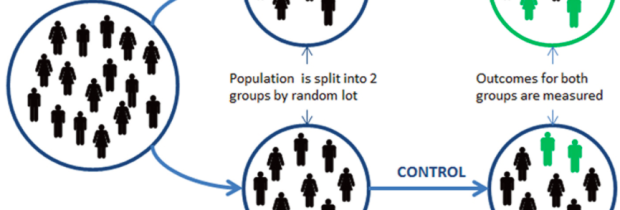

We need to be careful extrapolating out from (eg) RCTs to the general population: is it wise to expect the same results when applying an intervention more widely? Optimism bias is so much a ‘thing’ that it’s even in HM Treasury’s Green Book. I have heard Prof Kathy Sylva from Oxford be brilliantly challenging on this, in terms of the roll-out of some Early Years initiatives from the days before Sure Start. Even when the people involved in the trial were reporting directly to her, it was hard to get the managers or practitioners in the early education settings to reliably do exactly what they were supposed to do, when they were supposed to do it. Surprise surprise it become a whole lot harder to retain fidelity and thus efficacy when the programme was rolled out more generally.

I really like the development of the WWCs. But I’m worried that their outputs might be seen as alluring silver bullets, ‘simple’ fixes that get us out of dealing with all the complicated messy stuff. What if your practitioners aren’t as relationally capable as the ones in the RCT that proved efficacy of the intervention? What if citizens don’t want to turn up for your service offer? What if there are opportunities to break new ground and do something radically different? Just picking the ‘right’ manualised, RCT’d intervention may only be a small part of the task of working out ‘what works’.

What we also need is a commitment to co-designing implementation in specific localities, and co-producing outcomes with citizens (which is where much of the potential for innovation lies). Attentiveness to the wider conditions that influence the effectiveness of certain approaches is critical, as is helping people understand how to assess the relevance of research evidence and apply it to their own context. It all goes back to our PublicOffice fundamentals around the vital importance of listening and learning. Learning learning learning.